When CERN’s Large Hadron Collider – the city-sized particle accelerator buried under the Franco-Swiss border—turns on, it accelerates a beam of protons to about 99.999% the speed of light and smashes them into each other head-on, showering exotic, high-energy particles in all directions. Four massive particle detectors, at different points along the 17-mile ring of the collider, have front-row seats to these collisions, observing a new shower of particles every twenty-five nanoseconds.

One of these detectors is the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS). A five-story tall mass of magnets, sensors, and wiring, the CMS is “compact” only relative to other detectors on the ring. When particles are colliding, its ten million constituent sensors are constantly reading out data. Someone (or rather, some algorithm) has to figure out what that data means very quickly—within a few millionths of a second—and discard the less interesting bits, or storing all the data would rapidly become a Sisyphean task.

“It would be like trying to store the entire Internet,” says Isobel Ojalvo, an assistant professor of physics at Princeton and a member of the CMS collaboration. This problem will only multiply over the coming decade, as the collider ramps up its particle beams: The protons in the most recent LHC beams already are accelerated to nearly twice the energy as those which first revealed the Higgs Boson in 2012, and starting in 2027, the LHC will enter its “high luminosity” era, when beams producing 100 times as many collisions will aim to push physics beyond the standard model.

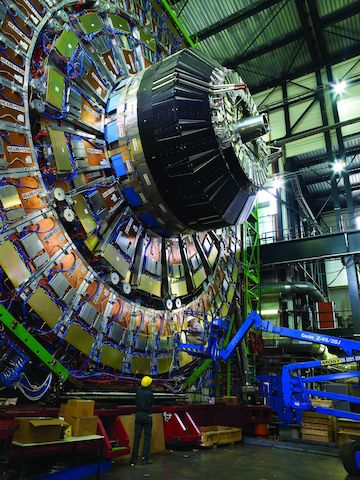

One endcap of the CMS Detector at the LHC. Photo Credit: CERN.

The task of preparing the computing systems of the LHC detectors for this deluge of data falls to a team of researchers with the Institute for Research and Innovation in Software for High Energy Physics (IRIS-HEP) headquartered at the Princeton Institute for Computational Science & Engineering (PICSciE) but distributed around the country. In 2018, the National Science Foundation announced funding for a unique sort of research program: an international team of physicists and software researchers would solve cutting-edge problems in computation and give detectors like CMS a software upgrade. IRIS-HEP brings together software engineers, computer scientists, and physicists from 18 institutions around the country to reimagine how detectors like CMS record, process, store, and analyze their data.

Central to this effort, says IRIS-HEP principal investigator and Princeton physicist Peter Elmer, are research software engineers (RSEs) whose skills and professional status give them the freedom to tackle long-lasting research projects. “You can’t go for big, data-intensive projects that will take five years or longer without the expertise and continuity that research software engineers provide,” he says.

Among these RSEs is Bei Wang, a member of the research software engineering group with Princeton Research Computing—a consortium of campus groups led by PICSciE and OIT Research Computing. Since then, she’s been working on making faster software for particle tracking—quickly processing the raw data from the detectors into the trajectories that various particles formed in the collisions took through the detector.

Many “exotic,” high-energy particles are formed in these collisions, including the Higgs Boson that CMS helped discover in 2012. But these tend to decay very quickly into more stable particles like electrons and their heavier cousins, the muons, which give CMS its name. High-energy physicists spend much of their time working backwards from data about these stable particles to understand what high-energy particles, just as cosmologists work backwards from data about our present-day universe to understand the Big Bang.

To pull the particle tracks from the inrushing data as quickly as possible, Wang is taking existing software for analyzing these tracks and “accelerating” it by adapting it to work on specialized chips. One type of chip is the GPUs, a type of processor specialized to deal with many parallel computations at once; Wang is working with physicists at Princeton, the University of California-San Diego, and Cornell University to re-write particle tracking software for GPUs.

Though her scientific training is in kinetic plasma simulations at extreme scale, it’s a task she’s well-suited for, having spent six years before she became an RSE working in Princeton’s astrophysics department and Princeton Plasma Physics Lab on similar problems. “It fit my background,” Wang recalls thinking when she joined IRIS-HEP. “I knew I could leverage what I’d been doing previously in a new project.”

Wang is far from the only research software engineer involved in IRIS-HEP. The field of high-energy physics has historically been a leader in integrating software engineering into its research institutions and practices. “It’s easier for big science projects to do this,” than for other fields, says Elmer, referring to fields like high-energy physics, astronomy, and space exploration, “because you already have this big hardware enterprise. The challenge is to make sure that software is recognized as a research product in the same sense as a publication, or making a new scientific instrument.”

Henry Schreiner, who joined PICSciE last year as part of the IRIS-HEP team, says that working with them has enabled him to keep advancing his teaching and research skills. Schreiner works on analysis systems, honing the toolsets physicists will use to analyze data coming out of the high-luminosity collider—but which also should be generally useful. For instance, high-energy physics uses histograms to manage much of its data, so Schreiner is working on a project called “Boost-Histogram,” making it easier for physicists used to working in the python language to manipulate histograms in C++. He regularly joins the PICSciE RSEs in group meetings where they help each other solve problems they’re facing—and make sure everyone keeps learning. “Training is a strong focus of IRIS-HEP and the RSE group here as well.”

A group photo of the IRIS-HEP team during the first annual retreat at FermiLab in September 2019.

Through IRIS-HEP and PICSciE, Wang has many opportunities to train Princetonians and physicists from across the country in the fundamentals of scientific computing. PICSciE’s Research Software Engineering group, which includes RSEs working not just on physics, like Wang, but also biology, sociology, and applied math, runs trainings throughout the year for Princeton students, and at IRIS-HEP’s annual CoDaS-HEP summer school, Wang and others introduce physicists to the basic principles of scientific computing: in 2019’s program, Wang presented on the basics of optimizing scientific software for speed and gave another talk called “Floating Point Arithmetic Is Not Real,” on the idiosyncrasies and pitfalls of perhaps the most common tools for doing arithmetic on computers.

In the RSE group, she says, “You can leverage your expertise but at the same time you keep learning new things, and that makes it interesting.”

Wang’s teaching and learning will come in handy for one of her upcoming IRIS-HEP projects: she will soon begin working with Ojalvo and her students to speed up the process of filtering interesting collision data out of the slew of uninteresting collisions using FPGAs, processors whose customizability means they may be even faster, for some purposes, than the GPUs Wang is currently working on.

Ojalvo is looking forward to working with Wang, she says, because her connections with other parts of IRIS-HEP and training experience will help get the project off to a flying start. “Having someone who has some knowledge and a history of doing this sort of work, who knows the full life cycle of the project, helps both with getting an individual project started more quickly, but also with training students to help them get off the ground. It’s really nice to have these sorts of resources readily available.”