The world’s biggest machine is getting a hardware upgrade. With it comes a historic transformation in data science.

Work is underway on several new components at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) that will significantly boost the proton beams’ intensity. These include superconducting magnets to precisely bend and focus the beams, radiofrequency cavities to maximize head-on collisions, and high-temperature transmission lines to deliver more power.

The LHC’s improvements are so extensive that, once completed, it will bear a new name: the High-Luminosity Large Hadron Collider (HL-LHC). Expected to begin in late 2027 and to continue through the 2030s, the high-luminosity era will enable more precise measurement of the Higgs boson. It will also help scientists look into rare B meson decays, potential dark matter candidates, and other phenomena thought to exist outside the Standard Model.

More proton collisions mean more data. The HL-LHC’s two general-purpose detectors, ATLAS and the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS), are expected to generate up to an exabyte each year, about 10 times as much as the data used to discover the Higgs boson in 2012.

An exabyte – one quintillion bytes – is enormous. It’s roughly the amount of data in 200 billion plaintext copies of the complete works of William Shakespeare, five trillion xkcd comics, or a Zoom meeting that lasts 100,000 years. If you were to begin stacking an exabyte worth of CDs, you would risk a collision with International Space Station before you were a quarter of the way through.

“This is an order of magnitude bigger than the data challenges we’ve faced in the past,” says Allison Hall, a Distinguished Researcher at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory’s LHC Physics Center. “We don’t want our computing capabilities to be the limiting factor for the scientific results.”

Meeting this challenge calls for a social transformation within the high-energy physics community, which has long developed its data-analysis tools and infrastructure in isolation. This transformation is already underway, as the emergence of large datasets and approaches to handling them in other communities means that high-energy physics no longer has to go it alone.

“As scientists, it’s important to learn from the examples of other people,” says Oksana Shadura, a software engineer at University of Nebraska-Lincoln based at CERN and a member of the Institute for Research and Innovation in Software for High Energy Physics (IRIS-HEP), which includes researchers from 17 institutions across the United States. “We cannot just close ourselves off to the world.”

Funded by the National Science Foundation and headquartered in the Princeton Institute for Computational Science and Engineering (PICSciE) at Princeton University, IRIS-HEP aims to serve as an intellectual hub for this transformation.

Peter Elmer, IRIS-HEP’s executive director and principal investigator, hopes that the institute’s efforts to develop new ways to manage and analyze data will extend beyond high-energy physics to “transform how the data science community works.”

“What ties us together is methodology,” he says.

Early adopters

The fundamental constituents of matter and the forces that govern them aren’t exactly known for drawing attention to themselves. Since the end of the Second World War, searching for them has increasingly become a matter of needles and haystacks.

“Historically, we were the first people to deal with datasets of this magnitude,” says Hall.

That’s why particle physicists were among the first scientists to embrace the digital computer. They were some of the earliest to use FORTRAN, the first high-level programming language. In 1963, Dutch particle physicist Martinus Veltman created Schoonschip, one of the first computer algebra systems. In 1989, in an effort to help scientists at CERN share data, software engineer Tim Berners-Lee created high-energy physics’ best-known technology transfer: the World Wide Web.

Since the 1950s, however, physicists and computer scientists haven’t communicated as much as they should have, says Princeton computational physicist and IRIS-HEP team member Jim Pivarski.

“There were great ideas in database theory that were largely unrecognized by physicists and data access and analysis techniques that weren’t even widely known outside of physics,” he says. “We had this insular community that neither imported nor exported.”

Jim Pivarski leading a hands-on tutorial at the CoDaS-HEP school at Princeton. Python, awkward arrays, and interactive analysis were major topics. Photo credit: Ma. Florevel Fusin-Wischusen, Princeton Institute for Computational Science & Engineering.

A “grassroots change”

But the period between CERN’s approval of the LHC’s construction in 1994 and the end of its first operational run in 2013 marked a societal sea-change in data usage. Billions of people went online. Cloud computing revolutionized storage and processing. Tech companies amassed colossal datasets, fueling the growth of machine learning algorithms and sophisticated analytics engines like Apache Spark. Other scientific fields, particularly astronomy, genomics, and Earth sciences, also began pushing the boundaries of data analysis. By the time CERN scientists announced the discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012, it was clear that high-energy physicists weren’t the only ones thinking about exabytes.

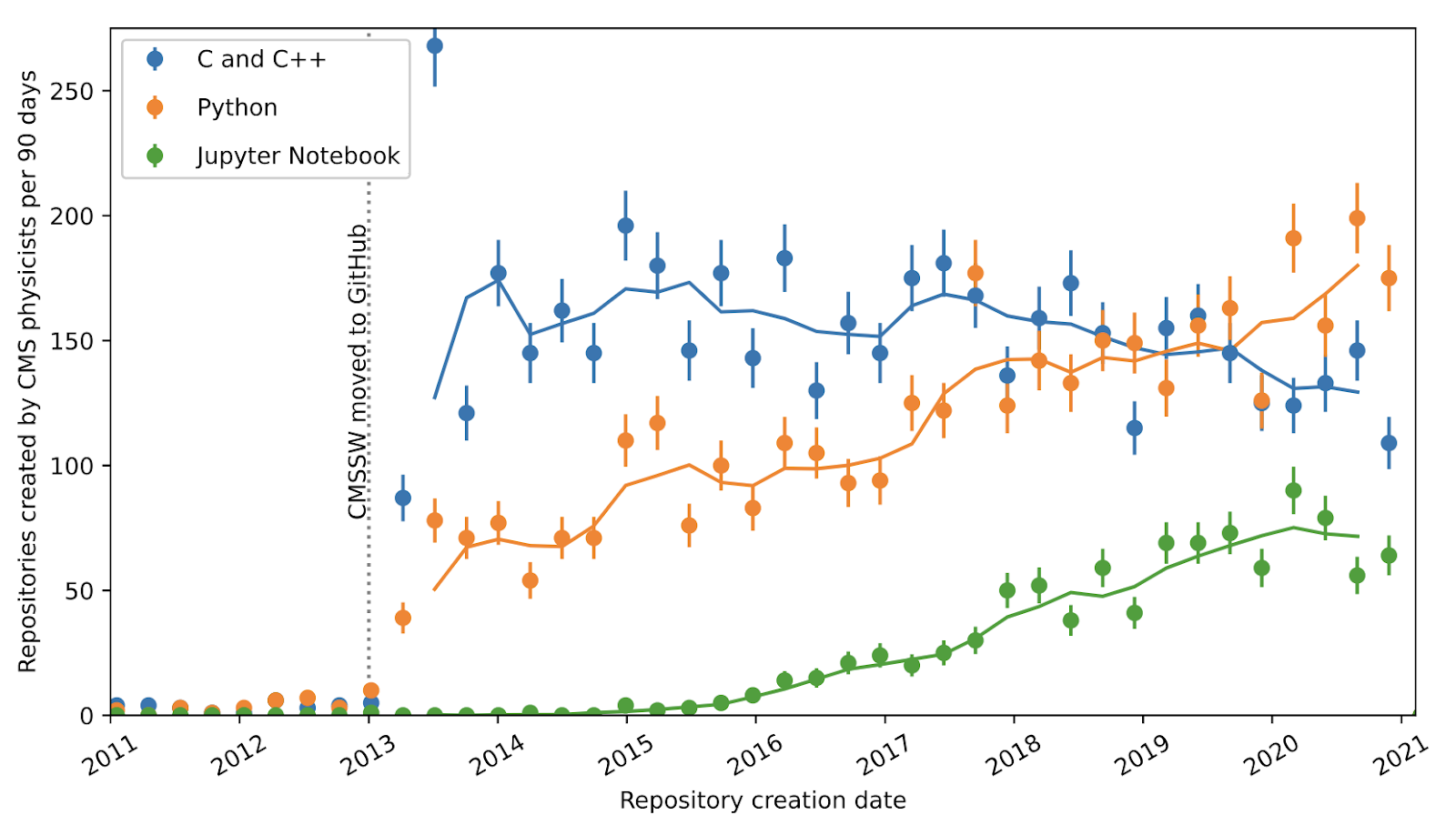

Since then, the high-energy physics community has been opening its doors to alternative tools for data analysis. In 2013, CMS physicists began using Github. According to Pivarski’s analyses of the software development site, they have since been increasingly adopting the open-source language Python. In 2019, Python surpassed C++ as the coding tool of choice among CMS physicists.

“It’s a bottom-up, grassroots change,” says Pivarski. “The people who are doing the analysis are just starting to use Python on their own.”

Part of the shift to Python, says Shadura, is its versatility. “Not all students and not all postdocs stay in physics,” she says. “In addition to data-analyst skills, they need to have something on their CV that they can more easily transfer to industry.”

Shadura says that having a vibrant Python-based ecosystem, one that includes popular packages like NumPy, Pandas, scikit-learn, and the data science web app Jupyter Notebooks, creates conduits between particle physics and other fields. “There is a huge flow between people going from industry to academy and from academy to industry,” she says. “And this flow is creating a kind of synergy.”

An awkward fit

Pivarski says that some of the new tools being developed to solve problems in particle physics also help data scientists in other disciplines.

“I’m hoping that it will be a two way street,” he says.

One of these problems arises from the nature of proton collisions. When protons collide, they don’t necessarily produce the same number of decay products each time. “You can have two muons in one event, one muon in the next event, and zero in the next event,” he says.

As a result, arrays describing a series of collisions are “ragged,” with columns of variable lengths. In the past, this raggedness has prevented high-energy physicists from adopting popular data-analysis frameworks, which are typically designed for rectangular arrays.

In 2018, Pivarksi and his colleagues developed a software library for handling these awkward arrays in NumPy, Python’s numerical computing package.

An analysis of the software development site Github by Princeton computational physicist and IRIS-HEP team member Jim Pivarski tracked the usage of software tools among physicists working on the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) experiment. He found that the programming languages C and C++ declined in popularity relative to the platform-independent, open-source tools Python and Jupyter Notebook. Credit: Jim Pivarski

It turns out that this solution can be repurposed for other scientific disciplines where awkward arrays are common. One example can be found in radio astronomy. The Square Kilometer Array (SKA) project, which aims to place thousands of dish receivers and millions of antennas in South Africa and Australia, is expected to gather up to an exabyte of raw data each day.

Radio telescope data is typically rectangular, but to compress this data, SKA’s data scientists “sparsified” the images by removing redundant information. “And that’s turned what used to be a square problem into a ragged one,” he says.

Pivarski agrees that growing familiarity with handling awkward arrays could help scientists in other fields collect data that would otherwise be unwieldy. An example from genomics: information about single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are often stored as Variant Call Format (VCF) files, which contain fixed fields for alternative alleles. But because each SNP can have multiple alternative alleles, researchers must arbitrarily set the field to a fixed number before loading it into a NumPy array.

“Your tools shape how you see the problem,” he says. “As non-physicists use it more, we’ll probably find that there are more of these problems that have been tucked away.”