The nucleus of the atom was discovered a century ago thanks to scientists who didn’t blink.

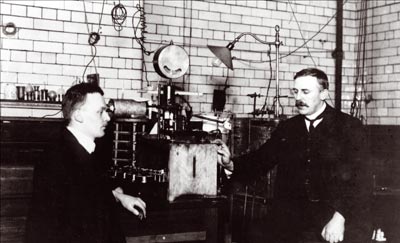

Working in pitch darkness at the University of Manchester between 1909 and 1913, research assistants Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden peered through microscopes to count flashes of alpha particles on a fluorescent screen. The task demanded total concentration, and the scientists could count accurately for only about a minute before fatigue set in. The physicist and science historian Siegmund Brandt wrote that Geiger and Marsden maintained their focus by ingesting strong coffee and “a pinch of strychnine.”

Modern particle detectors use sensitive electronics instead of microscopes and rat poison to observe particle collisions, but now there’s a new challenge. Instead of worrying about blinking and missing interesting particle interactions, physicists worry about accidentally throwing them away.

“Once we lose the data, we lose it forever,” says Georgia Karagiorgi, a professor of physics at Columbia University and the US project manager for the data acquisition system for the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment. “We need to be constantly looking. We can’t close our eyes.”

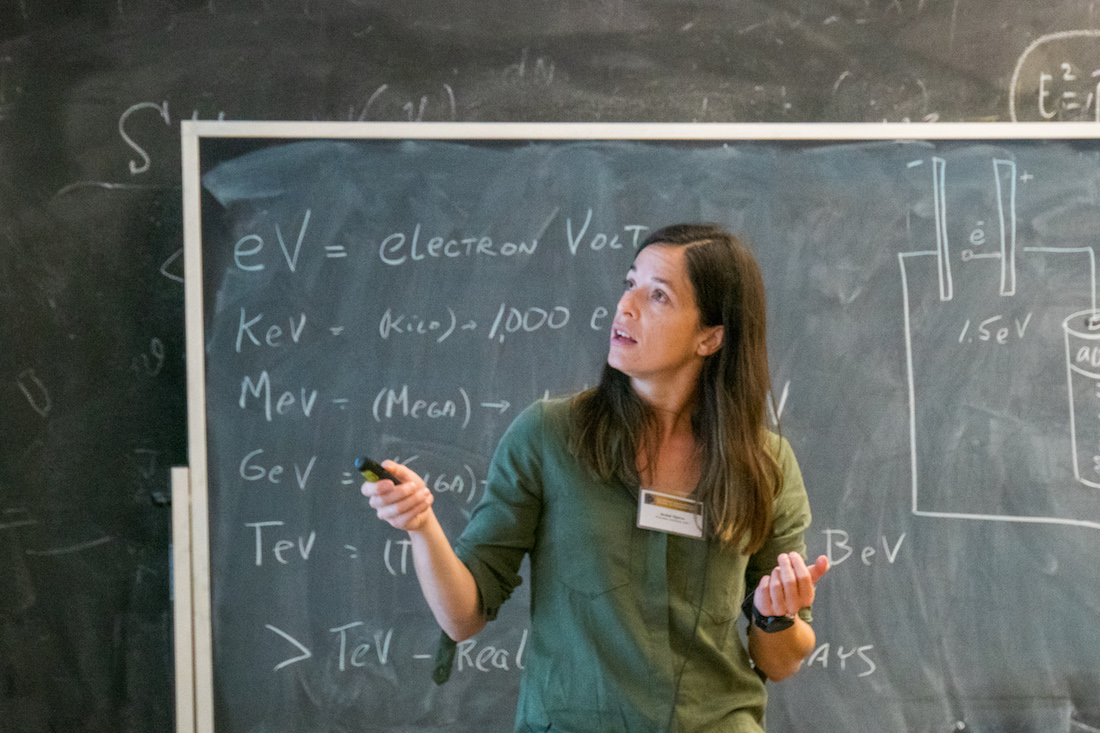

Isobel Ojalvo (Princeton University) discusses trigger systems for high energy physics. Photo Credit: Marguerite Tonjes (FNAL).

“At CMS we have a massive amount of data,” says Princeton physicist Isobel Ojalvo, who has been heavily involved in upgrading the CMS trigger system and is an associated faculty with the Princeton Institute for Computational Science & Engineering(PICSciE). “We’re only able to store that data for about three and a half [millionths of a second] before we make decisions about keeping it or throwing it away.”

The challenge of deciding in a split second which data to keep, some scientists say, could be met with artificial intelligence.

A numbers game

Discovering new subatomic phenomena often requires amassing a colossal dataset, most of it uninteresting.

Geiger and Marsden learned this the hard way. Working under the direction of Ernest Rutherford, the two scientists sought to reveal the structures of atoms by sending streams of alpha particles through sheets of gold foil and observing how the particles scattered. They found that for about every 8000 particles that passed straight through the foil, one particle would bounce away as though it had collided with something solid. That was the atom’s nucleus, and its discovery sent physics itself on a new trajectory.

By today’s physics’ standards, Geiger and Marsden’s 1-in-8000 odds look like a safe bet. The Higgs boson is thought to appear in only one out of every 5 billion collisions in the LHC. And scientists have only a small window of time in which to catch them.

Hans Geiger, left, and Ernest Rutherford display their equipment in their laboratory at Manchester University around 1908.

That’s why modern particle physics deals in volume. The LHC produces collisions at a rate of 40 million per second. To capture all the data from these collisions, you would need to acquire more than 140,000 one-terabyte storage drives, every hour.

It’s during these few millionths of a second that the first level of CMS’s two-tier trigger system winnows the potentially interesting events down from 40 million per second to 100,000 per second. The selected events are forwarded to the second tier, a farm of commercial computers that included more than 13,000 CPU cores. This high-level trigger has 150 milliseconds to further narrow down the candidates, before finally arriving at a manageable 1,000 events per second.

All told, in about half the time it takes a human to blink, CMS’s triggers have processed and discarded 99.9975 percent of the data.

The triggers will soon need to get even faster. In the LHC’s Run 3, set to begin in March 2022, the total number of collisions will equal that of the two previous runs combined. The collision rate will increase dramatically during the LHC’s High-Luminosity era, which is scheduled to begin in 2027 and continue through the 2030s. That’s when the collider’s luminosity, a measure of how tightly the crossing beams are packed with particles, is set to increase tenfold over its original design value.

Collecting this data is important because in the coming decade, scientists will intensify their searches for phenomena that are just as mysterious to today’s physicists as atomic nuclei were to Geiger and Marsden.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Phil Harris, speaks at the Fast Machine Learning workshop at FNAL, in 2019. Photo Credit: Marguerite Tonjes (FNAL).

A new physics

For the past five decades, high-energy physics has been guided by the Standard Model, a theory formulated in the early 1970s that describes 17 types of elementary particles – 12 fermions and five bosons – and predicts how they interact.

As theories go, it’s among the most successful in the history of science. The Standard Model has not only helped physicists understand the particles they had discovered, but it also described, with remarkable precision, the properties of those that had yet to be discovered. The last Standard Model particle to be detected was the Higgs boson, discovered at CERN in 2012.

But despite its success, the Standard Model contains huge gaps. For one thing, nobody knows how gravitation fits in. The same goes for dark matter, dark energy, neutrino masses, and why the universe seems to have started off with unequal amounts of matter and antimatter. What’s more, as measurements of particle interactions become more precise, physicists are noticing that some numbers seem a bit off. In April, for instance, preliminary results from the Muon g-2 experiment at the US Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory offered tantalizing hints that the muon may be interacting with a force or particle the Standard Model doesn’t include. Identifying these phenomena and many others may require a new understanding.

“Given that we have not seen [beyond the Standard Model] physics yet, we need to revolutionize how we collect our data to enable processing data rates at least an order of magnitude higher than achieved thus far,” says MIT physicist Mike Williams, who is a member of the Institute for Research and Innovation in Software for High-Energy Physics, IRIS-HEP, funded by the National Science Foundation.

Physicists agree that future triggers will need to be faster, but there’s less consensus on how they should be programmed.

“How do we make discoveries when we don’t know what to look for?” asks Peter Elmer, executive director and principal investigator for IRIS-HEP. “We don’t want to throw anything away that might hint at new physics.”

There are two different schools of thought, Ojalvo says.

The more conservative approach is to search for signatures that match theoretical predictions. “Another way,” she says, “is to look for things that are different from everything else.”

This second option, known as anomaly detection, would scan not for specific signatures, but for anything that deviates from the Standard Model, something that artificial intelligence could help with.

“In the past, we guessed the model and used the trigger system to pick those signatures up,” Ojalvo says.

But “now we’re not finding the new physics that we believe is out there,” Ojalvo says. “It may be that we cannot create those interactions in present-day colliders, but we also need to ask ourselves if we’ve turned over every stone.”

Advocacy for so-called theoryless searches remains a minority opinion in the physics community, says MIT physicist Philip Harris, but they present a promising avenue for artificial intelligence. “The algorithms will be able to recognize the beam conditions and adapt their choices,’’ he says. “Effectively, it can change itself.”

Instead of searching one-by-one for signals predicted by each theory, physicists could deploy to a collider’s trigger system an unsupervised machine-learning algorithm, Ojalvo says. They could train the algorithm only on the collisions it observes, without reference to any other dataset. Over time, the algorithm would learn to distinguish common collision events from rare ones. The approach would not require knowing any details in advance about what new signals might be, and it would avoid bias toward one theory or another.

MIT physicist Philip Harris says that recent advances in artificial intelligence are fueling a growing interest in this approach—but that advocates of “theoryless searches” remain a minority in the physics community.

More generally, says Harris, using AI for triggers can create opportunities for more innovative ways to acquire data. “The algorithm will be able to recognize the beam conditions and adapt their choices,” he says. “Effectively, it can change itself.”

The LHCb experiment is well suited to helping scientists understand the apparent discrepancy between matter and antimatter at the beginning of the universe. Credit: CERN

The eye of the beholder

Not all triggers are identical, however. LHCb specializes in beauty quarks, short-lived particles thought to have been abundant in the early universe and whose behavior might help explain the asymmetry between matter and antimatter. Unlike CMS, which encircles its sensors around the proton-beams’ crossing, the LHCb experiment deploys a series of detectors ahead of the beam intersection to spot particles that are thrown forward, which often happens to some hadrons that contain beauty quarks. That means it faces fewer data demands.

MIT Professor Mike Williams worked on the Allen project, a GPU-based trigger system for the LHCb experiment. Credit: MIT

For Run 3, LHCb’s trigger, which has used AI from the beginning, will now attempt to capture every collision. That means that it won’t need to rely on AI algorithms to decide what events to keep, says Williams. “Rather than move AI upstream into the detector electronics where the first decisions are made, we have moved the decision-making downstream to where the data are processed — and where AI and other techniques are readily available.”

IRIS-HEP has played a key role in helping to develop LHCb’s new trigger. Known as Allen, after the renowned American computer scientist Frances Elizabeth Allen, the trigger consists entirely of graphics processing units (GPUs). Originally built to render images, particularly for video games, the massively parallel architecture of GPUs make them well suited for real-time processing in high-energy physics .

“Allen is now capable of processing LHCb data in real time in ways that we never expected to be possible even a few years ago,” says Williams. “The Allen team has so many dedicated developers and I am constantly amazed by the improvements in performance they keep managing to achieve.”

Underground astronomy

The DUNE experiment, scheduled to begin collecting data in 2025, is an international collaboration with detectors at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) near Batavia, Ill., and the Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF) in Lead, South Dakota. It aims to better understand neutrinos, the ubiquitous yet barely perceptible particles that stream constantly from stars and other nuclear reactions.

From a cavern nearly a mile below the Earth’s surface, the SURF detector will examine neutrinos from two main sources. One will come from an intense beam of neutrinos fired from a particle accelerator at Fermilab, more than 800 miles away. The other will come from supernovas.

SURF’S underground neutrino detector, the world’s largest, consists of a 70,000-ton volume of liquid argon. When neutrinos strike atoms in the liquid, they briefly excite them to higher energy states. When the atoms settle down again, they can release particles that collide with other argon atoms and strip them of electrons. This allows the detector to sweep the liquid with an electric field and then reconstruct a 3-D image of each neutrino’s trajectory.

Located at CERN, the ProtoDUNE detector aims to test different electronic components for the US-based DUNE experiment, whose detector will be 20 times larger. Credit: CERN

These images, however, are huge, which means that DUNE faces a data challenge similar to the LHC. “The total rate of the video stream is five terabytes per second, and we can only store 30 petabytes per data per year,” says Karagiorgi. That means that if no data were discarded, the yearly storage capacity would be filled in 10 minutes.

Columbia professor Georgia Karagiorgi is the US project manager for the data acquisition system for the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment. Credit: Columbia University

This is particularly vexing for studying supernova neutrinos. Because they arrive unexpectedly, the detectors need to be recording all the time. What’s more, they carry far less energy than the ones that will originate from Fermilab’s accelerator and are therefore harder to spot.

“They’re very difficult signatures to decipher,” says Karagiorgi. “They look like tiny little blips in what otherwise looks like static noise on old CRT TVs…The more intelligent the algorithm is, the better you can fish those out.”

But because the detector uses image recognition, its trigger can benefit from advances in the computer vision community. One potential solution that Karagiorgi has been pursuing is to use convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which have been used in applications ranging from video analysis to archaeology.

Karagiorgi says that CNNs perform well in simulations, but she cautions that more work is needed. “All of this is wonderful in theory,” she says, “but in real life once you have your detector running, there are all sorts of effects that you’re not able to simulate.”

As with the triggers for CMS and the LHCb experiments, programming DUNE’s triggers requires making tradeoffs between efficiency, breadth, accuracy, and feasibility.

“It’s all about hardware resource constraints, power resource constraints, and of course cost,” says Karagiorgi.

“Thankfully,” she adds, “we don’t need strychnine.”

* A version of this article appeared in Symmetry Magazine.