At the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), scientists are crashing together fundamental particles at high speeds in search of answers to questions about the nature of the universe. Reconstructing the trajectories of the particles in the collider is one of the most resource-intensive parts of the experiments at the LHC or any high energy experiment. A fast and high performing particle tracking software is required to recreate the tracks of the particles while also revealing other important properties of the particles. Yet, instead of having one efficient software to reconstruct the tracks of all high energy experiments, the code has been traditionally written on an experiment by experiment basis.

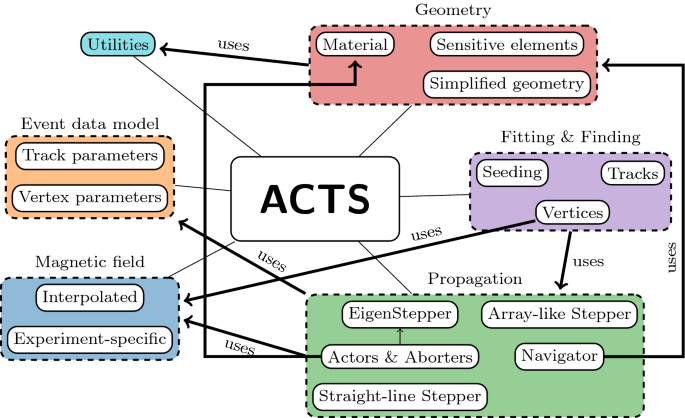

Enter ACTS, an international software collaboration that began at CERN which is developing a suite of modern track reconstruction tools. Notably, the project is open-source – available to scientists working on a variety of projects. At the IRIS-HEP collaboration, an array of researchers are working together on the ACTS project to bring fast and efficient software to experiments of all sizes, including those which may not have had access to advanced software otherwise.

“It gives an opportunity to smaller experiments to be able to profit from algorithms where they wouldn’t have the resources to develop that themselves,” said Heather Gray, an associate professor at the University of California, Berkeley.

An ACTS workshop runs out of University of California, Berkeley. Photo credit: Heather Gray

What is ACTS

Typically in the past, researchers would write their own particle tracking software on an experiment by experiment basis. This meant there was a vast array of particle tracking software, but each was specific to the original experiment it was created for and not necessarily suited for use for other projects.

“It’s kind of like wasting resources because you’re using the same kind of software but you’re using it for different experiments,” said Rocky Bala Garg, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University. With one software being used by many different projects, Bala Garg points out it will be better maintained and developed, among other benefits.

While there were clear benefits to creating a software which could be used across experiments, Gray said it’s not an easy task to make it available. “Tracking software itself is quite a complicated piece of code,” said Gray. The fact that the team had access to modern tools and software paradigms is what allowed them to create software which can work on different experiments and perform well.

Gray said the concept for a common tracking software which would be “experiment agnostic” was built into the idea for ACTS from the beginning. The idea for ACTS began with physicist Andi Salzburger of the ATLAS experiment at CERN, which is using the LHC to probe questions on the fundamental building blocks of our universe. Researchers with IRIS-HEP began working on the software in 2018.

“The main goal of the software is to improve upon the current software,” said Bala Garg. “For the upcoming, more complex tracking environments, or the High Luminosity LHC and in other experiments, these traditional software may not be as useful as they are right now.”

One way the team is improving the software is by exploiting new software structures. ACTS was written for the computer processing unit (CPU), which is the main processor of a computer. But most laptops or PCs have a specialized graphics processing unit (GPU) which has the ability to run several smaller tasks at the same time.

Beomki Yeo, a postdoctoral researcher with Gray at the University of California, Berkeley, is writing algorithms to convert ACTS into a new format for the GPU. With the GPU, the software will perform the same job but faster and with lower power consumption. “You want to make things faster and also you want to save money and power and energy,” said Yeo. “That’s the fundamental purpose of our project.”

Many other particle tracking software packages are written in outdated software frameworks, which are often difficult for current programmers to edit and update. “By redesigning ACTS and by being able to write it from scratch, you get to make it naturally fit into the paradigm of these more modern languages,” said Gray.

The researchers are still developing ACTS, but globally different high energy physics experiments have already begun showing interest in and even using the software. “I think that’s the best way to see what people think about ACTS,” said Gray. “If they’re actually interested and want to use it.”

Using ACTS

The Light Matter Dark Experiment (LDMX) at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is already adopting ACTS. Pierfrancesco Butti, a project scientist at SLAC said he expected ACTS to provide him with the basic algorithms and suite of tools which could be plugged into his experiment so that he can focus on the physics and not worry about developing his own software.

Butti said he thinks people started to realize in recent years that trying to “reinvent the wheel” for every experiment was not efficient. So far, his experience with ACTS has been both very positive and valuable. “Making this available to different experiments is fundamental because it’s going to speed up the way to arrive at the final results,” said Butti. “I think it’s a great concept.”

In tracking experiments, the analyses depend on the software which in turn tends to have many different parts. With an experiment agnostic software platform, researchers have the opportunity to plug in their own configurations relevant to their experiment and see what works best for them. Lauren Tompkins, an associate professor at Stanford University, said she likes that ACTS provides the freedom and flexibility to try out new things. “I really like that ACTS gives us a platform where we can develop stuff and then we can go and feed it back into the experiments,” she said.

Tompkins believes ACTS will provide real benefits to experiments both big and small. For smaller experiments, ACTS provides researchers with more advanced software than they would’ve been able to otherwise. For a larger experiment such as ATLAS at CERN, Tompkins said ACTS is already working as a testing ground for researchers to test and compare new algorithms. “ACTS is a paradigm that allows us to move forward as a community,” said Tompkins. “It’s just really great to be able to do something that works across experiments.”