(Originally posted here Reposted with permission from the Princeton University, Office of the Dean for Research)

In March of 2022, a student in Ukraine sent an email to the Princeton University physics department. The 18-year-old, Oleksandr Shelestiuk, soon received a response from Chris Tully, Princeton professor of physics and researcher at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), where scientists congregate from all over the world.

“I saw a great opportunity there to help get students out of harm’s way,” said Tully, who has hosted students at CERN through summer programs for over two decades. “I realized that the best way I could help them continue to be able to study and not be in danger was to try to get them to CERN.”

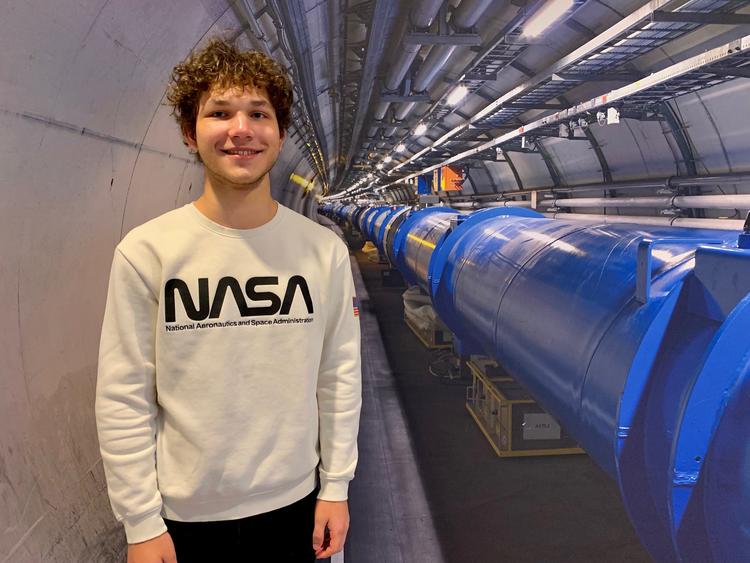

Oleksandr Shelestiuk in the tunnel leading to the CMS detector, in front of an image of a dipole.

Eighteen-year-old Oleksandr Shelestiuk found a way to evade the disruption to his life and education in Ukraine by pursuing research with Princeton faculty at CERN. Photo credit: Steven Goldfarb

Around the same time, Peter Elmer, senior research physicist at Princeton and executive director of IRIS-HEP, a software institute funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) to develop innovative software upgrades for experiments at CERN, began leveraging his own summer program to provide remote research opportunities for Ukrainian students.

When they realized their overlapping goals, Tully and Elmer applied together for a grant from the Simons Foundation to support students displaced by the war. By early spring of 2022, Tully found housing accommodations for three Ukrainian students near CERN in France, and, soon after, was able to welcome a fourth student thanks to support from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

Shelestiuk and schoolmates Mariia Tiulchenko and Fedir Boreiko, all students at the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, left their homes in April of 2022 hoping to further their science and engineering skills, and someday help rebuild the country they left behind.

“Leaving was a mixed experience for me. I had to leave my family not knowing when I would see them again,” said Boreiko, whose hometown of Odesa underwent heavy attacks only days before he left. “But I think of the chance I was given and of my responsibility to all of those people who are still in Ukraine, and I’m inspired to carry on in pursuing my education.”

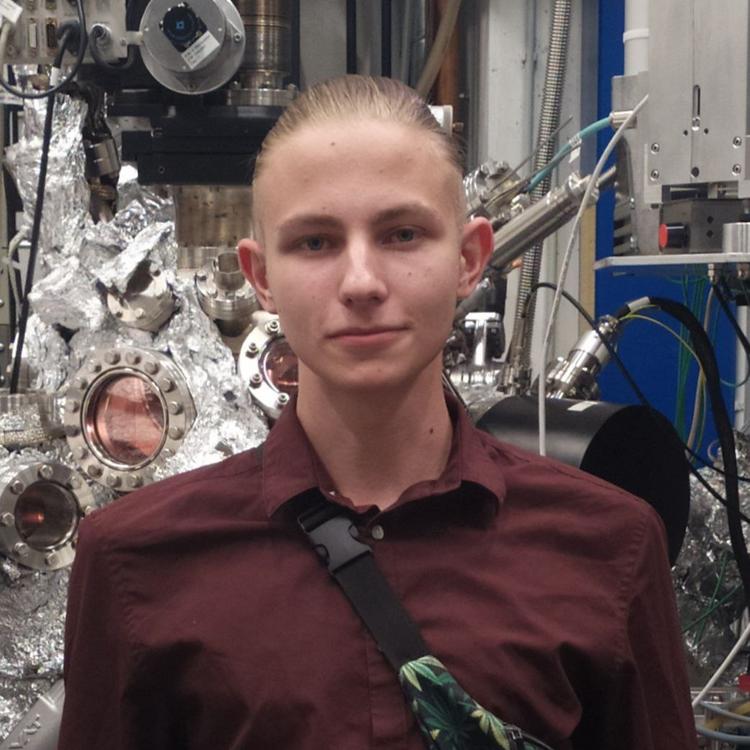

Artem Havryliuk works remotely with IRIS-HEP as he pursues his master’s degree in engineering and applied physics. Photo credit: Bohdan Semeniuk

The donation from the Simons Foundation funded four in-person students, as well as internships for twenty other remote students who remained in Ukraine doing research with the IRIS-HEP software institute.

“This internship changed my vision of what I want to do in life,” said Artem Havryliuk, IRIS-HEP fellow and graduate student at Kyiv Academic University. “I’ve found that I can combine my love for physics with my interest in programming, and I want to continue on this path of using machine learning to solve scientific problems.”

At the frontier of research

Particles in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN collide every 25 nanoseconds, producing far more data than the detectors can store. The three schoolmates Tiulchenko, Shelestiuk and Boreiko worked closely with Tully last summer to optimize the hardware, called the trigger system, that automates decisions about what data to store and what to throw away for the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) detector, one of four major particle detectors at the LHC. Scientists analyze this data to uncover new laws of physics and learn about the structure of the universe.

“We all worked together as a team to tackle complex problems,” said Shelestiuk, who has been interested in physics since his first exposure to it in high school. “The work we did this summer really helped me determine what I’m interested in working on, and I gained a lot of new experience with both physics and computer science that will help me in the future.”

Boreiko, Tiulchenko and Shelstiuk sitting together at a laptop. Along with their research, Boreiko, Tiulchenko and Shelstiuk (left to right) studied topics including cosmology, high energy physics and computer science over the summer. Photo credit: Steven Goldfarb

Tully said each of the students made valuable contributions to his group’s research projects over the summer. “They really had a different experience of how to think about physics and math,” he said. “They ended up solving problems in different ways than I thought they would, and they were able to communicate what they did.”

The students attended lectures throughout the summer, covering topics including the structure and components of the CMS detector, as well as topics in cosmology, high energy physics and computer science.

“Above all, what we tried to do is teach students something that seems impossible to learn – how to solve problems that have never been solved before,” Tully said. “That is frontier research, and they’ve all done very well.”

The tools to rebuild

Amidst global conflict, CERN researchers and administrators advocate for the use of science as a tool for positive change. CERN was founded by European countries that came together despite global conflicts in the wake of World War II, and continues to function as grounds where researchers from all nations collaborate for the benefit of humanity. The institute welcomes researchers from all backgrounds, including scientists from Russia, to uphold the institution’s commitment to scientific research and collaboration.

“A huge part of the concept behind CERN is that we can abstract away from national politics, and essentially connect scientists in ways that are entirely separate,” Elmer said.

Tully hopes that this program will aid in the long-term growth and longevity of science in Ukraine. “This could be a great way in which we can help the Ukrainians rebuild their science programs, and to demonstrate the efficacy of encouraging undergraduate level students to engage with research early on, especially when they see how successful these students have been,” he said.

Tiulchenko, Shelestiuk and Boreiko were each accepted by a program run by the University of Michigan that provided them with funding to continue their studies at CERN throughout last fall and spring. Tiulchenko and Shelestiuk remain at CERN working with Chris Tully again, and Boreiko is in New York City working on a machine learning project as an intern with the Simons Foundation. Mariia Tiulchenko was recently offered transfer admission by Cornell University with a full tuition package.

Mariia Tiulchenko in front of a multi-story image of the CMS detector interior. After completing her education, Mariia Tiulchenko plans to one day return to Ukraine to teach science. Photo credit: Steven Goldfarb

“I hope to first get my base of education and skills,” said Tiulchenko, who wants to one day return to Ukraine to teach. “I don’t know if I’ll go into physics, or if I’ll switch to studying artificial intelligence or programming, or a combination. But I know that I wish to have a positive influence on people who may want to learn these things as well.”

Shelestiuk shares a similar sentiment. “I hope that one day I’ll return to Ukraine. But for now, I need to be sure that I can help my country, or at least my family, by focusing on developing a strong enough education to do so.”

Boreiko said he hopes to one day publish research papers and educational materials in Ukrainian. “Historically, the language was repressed,” he said. “I think the best thing I could do is inspire others in Ukraine to pursue science.”