How did the universe begin? Why is there something instead of nothing? What is reality composed of at the smallest of scales?

These are just some of the profound questions that high-energy physics seeks to answer. To get closer to the answers, the field needs new generations of talented researchers able to wield the latest in software technologies to parse ever larger and more complicated datasets.

Nurturing this next generation is a goal of the Institute for Research and Innovation in Software for High Energy Physics (IRIS-HEP), a $25M software institute funded by the National Science Foundation and headquartered within the Princeton Institute for Computational Science and Engineering (PICSciE). Through the IRIS-HEP fellowship program, undergraduate students get the chance to work on projects that develop their programming skills.

This story is the second in a series about gap year IRIS-HEP fellows and how the program has helped shape their careers.

For Yuka Ikarashi (née Takahashi), IRIS-HEP was in many ways a transformative experience. The program gave her valuable international experience in computing academia, culminating in her coming to the United States to pursue a Ph.D. in Computer Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 2020.

While back in high school in her home country of Japan, Ikarashi recalls how her initial interests had actually tended toward physics, courtesy of physicists from The University of Tokyo making a recruitment visit. The pitch worked—Ikarashi successfully applied to the university in 2015, thinking physics was her future.

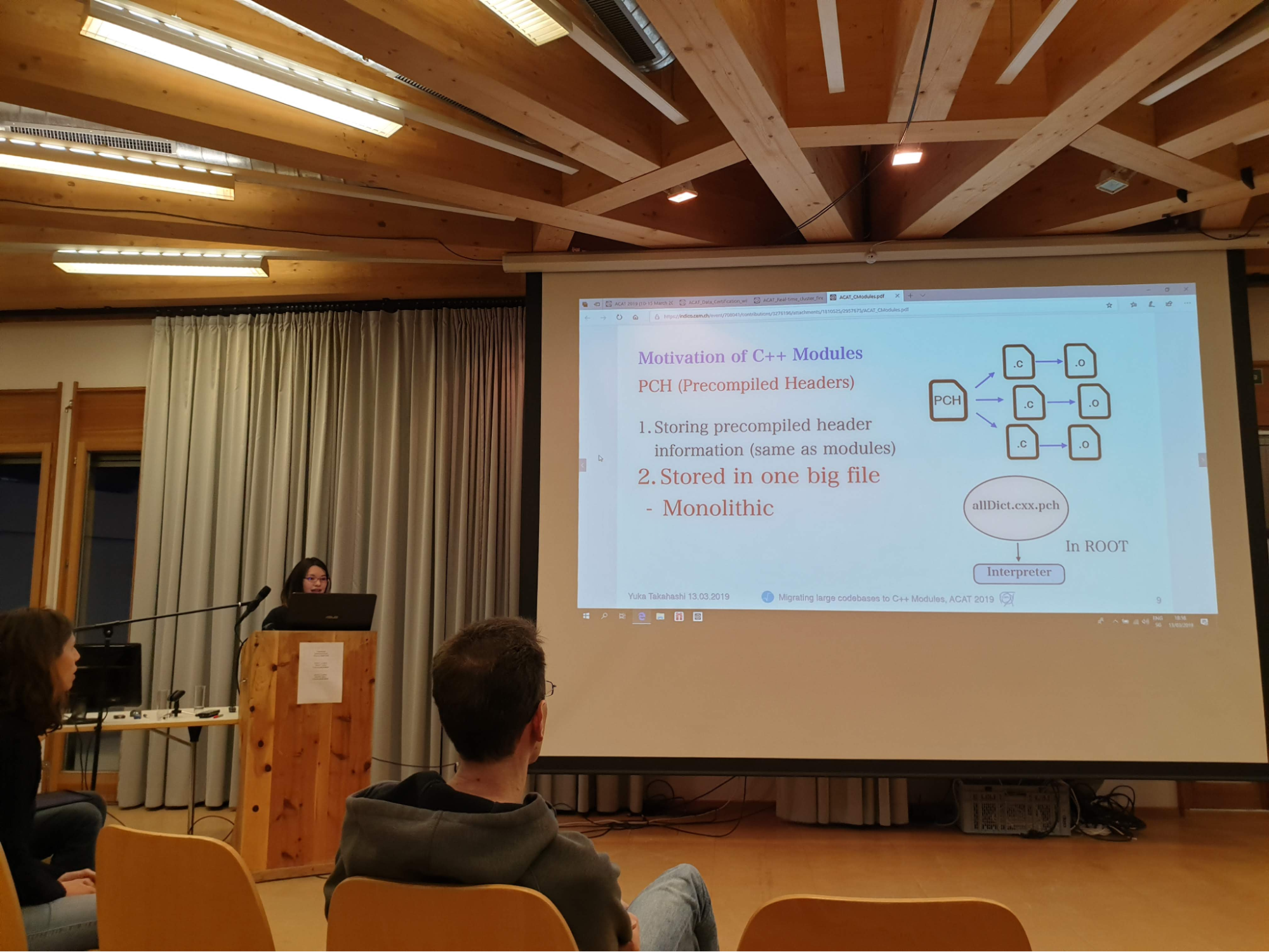

Yuka Ikarashi presenting at the 19th International Workshop on Advanced Computing and Analysis Techniques in Physics Research (ACAT 2019) in Saas Fee, Switzerland. Photo Credit: Oksana Shadura, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Yet computing ultimately won out. As it happened, the group of friends Ikarashi made at university were heavily into computer science. She joined them in a “Capture the Flag”- style computer security contest, which made quite an impression. “That was, like, a very geeky, nerdy experience,” Ikarashi jokes. “But also, it’s just fun, right?”

“So I didn’t end up doing physics,” she says, “and I chose CS [computer science], because I liked doing programming.”

Her choice was further validated in summer 2017 after her sophomore year, when she gained key experience in programming as a Google Summer of Code student. Her summer project was related to the LLVM Project—a set of modular and reusable compiler and toolchain technologies that collectively convert instructions into computer-readable and -executable code in software form.

While working remotely for the project, Ikarashi met and was mentored by Vassil Vassilev and Raphael Isemann, who collaborated with IRIS-HEP and also worked at CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research) in Switzerland. Recognizing her talent, Vassilev encouraged Ikarashi to join him in Europe at CERN.

Ikarashi followed through, deciding to take a gap year from her studies at The University of Tokyo. She moved to Geneva and worked at CERN from March 2018 to February 2019 as a research and development engineer, initially supported by DIANA/HEP (an NSF-funded precursor project which led to IRIS-HEP’s Analysis Systems area) and then IRIS-HEP itself.

As a world leader in physics, hosting around 2500 employees and thousands of visiting scientists, CERN proved to be a horizon-expanding experience for Ikarashi. “CERN is a very special place where people from different countries and universities naturally collaborate,” says Ikarashi. “It’s the opposite from a[n academic] silo.”

While there, Ikarashi primarily focused on an open-source framework, known as ROOT, often used by particle physicists for data analysis and visualization. More specifically, Ikarashi worked on performance engineering aspects, making customized interpreters—a kind of program that translates code line-by-line for direct execution.

Much of the time, for efficiency’s sake, related programs called compilers are used, which—as their name suggests—translate an entire set of instructions and compile it together into machine-readable code for execution. Interpreters, while slower, are more fastidious and thus better catching errors—commonly called bugs—as they parse each line. In this way, interpreters are of great help to physicists, who might not be deeply versed in code-writing, accurately conduct their analyses. “We wanted to give physicists the ability to inspect the values and the types of their code as they write instead of compiling everything ahead of time,” says Ikarashi.

Contributing to a major project with a multitude of users around the world was highly illuminating for Ikarashi. “Getting a sense of how ‘Big Science’ works was very interesting, because if you’re just working on computer science and software, usually the scale of the project is not so big,” she says. “The scale of this CERN project was much, much more massive than any project that I was familiar with in terms of software. Just being a part of that large ecosystem was very life-changing.”

Yuka Ikarashi during a visit to the University of Washington in September, 2024. Photo Credit: Peter Elmer, Princeton University.

Being in the professional research environment of CERN inspired Ikarashi to strive. “Usually as an undergrad, you don’t get much exposure to meeting PhD students and postdocs and people who are very senior, right? But that was exactly the environment that I was in; like everyone except me had a PhD in the office!”

The many conversations with her CERN colleagues about their careers greatly informed her decision to pursue a PhD herself. “I got the realistic sense of what a PhD gave them and then I could decide—not by kind of romanticizing having a PhD—but I could actually see the reality and decide for myself what I want to get out of this experience,” she says. “So that was the other part that was very crucial for my career.”

After graduating next year, Ikarashi plans to remain stateside and pursue an academic position. She strongly credits the IRIS-HEP experience with helping her get into MIT and advancing her professional ambitions in this regard. “I wouldn’t have been able to be a PhD student in the United States if I didn’t do the IRIS-HEP internship,” she says. “I’m eternally grateful for the opportunity that I got working at CERN through IRIS-HEP.”