The biggest machine ever built, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), is getting supercharged. In a few years’ time, particles will start smashing particles together inside the experiment’s 27-kilometer-long ring as part of the High-Luminosity LHC (HL-LHC), a planned upgrade that will deliver 10 times more data than the original collider. This anticipated data avalanche will pose major analytical bottlenecks for researchers as they sift for new insights and hopefully breakthroughs in physics.

To facilitate these efforts, an international team recently undertook an exercise geared toward dramatically boosting data flow rates for HL-LHC analyses. The exercise, called the 200 Gbps Challenge — referring to gigabits per second (Gbps), or billions of bits of data transmitted across a network—successfully demonstrated ways to achieve this goal, which represents a speedup on the order of 10—100 times over what is presently available. “What we’re accomplishing with this Challenge is simulating what physics analysis will be like in the HL-LHC era,” says Alex Held, a research scientist at the University of Wisconsin—Madison’s Data Science Institute and a co-coordinator of the 200 Gbps Challenge. “We’re laying the groundwork and infrastructure to satisfy the analysis needs of physicists in the future.”

In practice, data rates of this 200 Gbps caliber will mean that many physicists can conduct their analyses in near real-time, versus having to wait sometimes for days for data processing to occur as is typical currently—a discovery-slowing process that would become even more onerous given the HL-LHC’s gargantuan data output.

“A phrase you’ll often hear bandied about is “time to science’ or “time to insight,’ where we want to reduce that time it takes for a person to analyze data,” says Carl Lundstedt, the Grid System Administrator at the University of Nebraska’s Holland Computing Center, a participating facility in the 200 Gbps Challenge. “The analysis process is very iterative, and if those iteration steps take a long time, it can really obscure the science that the physicist is looking for.”

“We don’t want to go into a situation where we have data coming off the HL-LHC and the analysis pipeline isn’t ready for the physicist to do science,” Lundstedt added.

The 200 Gbps Challenge was fostered by the (Institute for Research and Innovation in Software for High Energy Physics IRIS-HEP, an institute headquartered in the Princeton Institute for Computational Science and Engineering (PICSciE) at Princeton University.

For the exercise, researchers sought to analyze 25% of a 180-terabyte dataset in 30 minutes. The HL-LHC is expected to routinely generate such massive datasets describing the particle shrapnel produced by collisions of protons or heavy ions, such as lead, detected within the experiment’s main instruments.

Two of those instruments are CMS and ATLAS, each of which is roughly the size of a multi-story building. Nebraska, mentioned prior, hosts a research group that works extensively with CMS. A second research group that participated in the 200 Gbps Challenge is at the University of Chicago, with ATLAS data analysis being their specialty. Each facility was selected to participate in the Challenge because they work with different LHC detectors while also conveniently possessing varied data analysis infrastructures and capabilities, allowing the team to explore diverse strategies for obtaining 200Gbps.

The primary components in play for data analysis are central processing units (CPUs), where number-crunching data decompression takes place, and the networks over which data flows to end users. “Broadly speaking, at University of Chicago, we have lots of CPUs, but we’re limited by the network,” says Held. “In Nebraska, we have fewer CPUs and instead the network is amazing. So we had to look at different approaches to hit our very aggressive 200 gigabit target.”

An initial problem affecting analyses at both sites: the globally distributed nature of LHC and eventual HL-LHC data. Pulling that data together quickly is often not possible. “Reading data from Australia to Chicago might not always be very timely because you’re inherently limited by how fast of a connection you have,” says Held. “Plus, if you’re reading data from a hundred different sites all across the globe, one of them might be down for maintenance at any point of the day, and that holds things up.”

To combat this issue, the Challenge team established a large system of data caches, so relevant data could be read once and then stored near where it would be needed for analysis. “You have immediate access to data and it’s very stable and very fast,” says Lincoln Bryant, a Linux System Administrator at the University of Chicago involved in the Challenge.

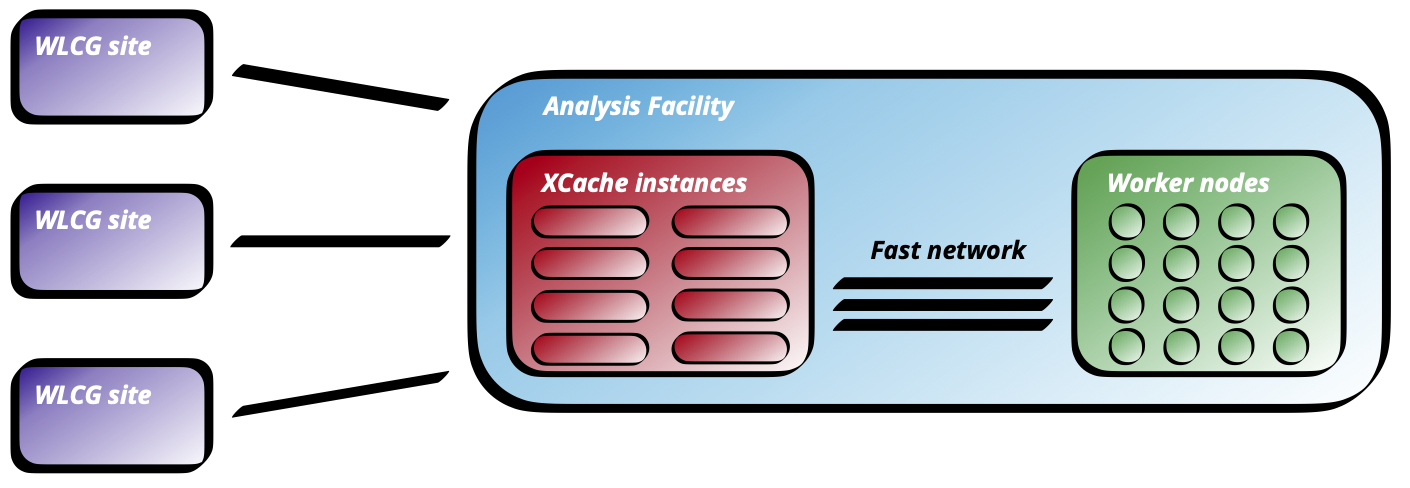

A depiction of key ingredients in the data flow: data starts out distributed across the Worldwide LHC Computing Grid (WLCG) and is ingested into a facility through a set of XCache instances acting as caches. Credit: https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.15464

Optimizing speed at the University of Chicago site required examining the network diagram and moving server racks and other hardware around to ensure there were no bottlenecking slow links. “For instance, you might have network paths that are only connected at 40 gigabits, and we have to deepen these or reorganize how the cluster is set up to enable 200 gigabit workflows,” says Bryant.

On the software side, the team sought to maximize benefits from parallel computing, where many portions of a data set needing analysis are handled simultaneously and integrated at the end. To effectively fan out and manage these portions, especially those that are interdependent, the team’s software engineers turned to dynamic task scheduling programs such as Dask, an open source project, and TaskVine, developed at Notre Dame University.

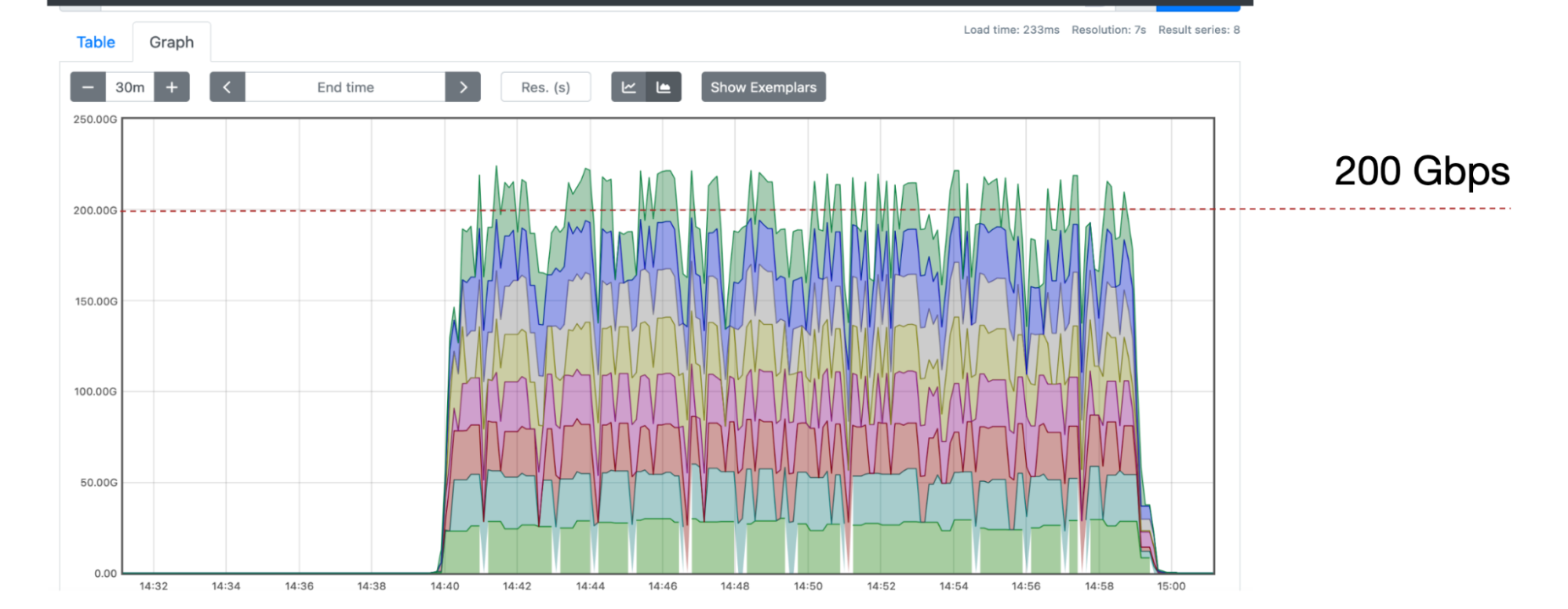

With the attentive deployment of these scalable computing libraries in sync with the rearranged hardware, the Challenge team demonstrated sustained data flow rates at 200 Gbps, illuminating a path forward for next-generation HL-LHC data analysis.

Throughput rate of the XCache servers in Flatiron at Nebraska, each color representing one of the eight XCache servers clearly indicating a sustained rate in excess of 200 Gbps. Credit: Oksana Shadura (University of Nebraska - Lincoln)

“There’s an overall goal in our field of high-energy physics of moving as far as possible in the direction where the bottleneck is not a researcher waiting for computing to happen, but instead where the researcher is carefully looking at results, making sense of them, and figuring out next steps,” says Held. “We’re helping to meet that goal and setting the stage for a highly productive HL-LHC run.”

Looking ahead, the team will continue working on increasing the reliability of their 200 Gbps approach, which after all was hammered out only over the span of an intensive several-week period last Spring. Due to the disbursing of many small tasks during the massive parallel computing process, errors that crop up in one task can lead to downstream problems. This issue is also commonly encountered and dealt with in conventional analyses, but Held and colleagues hope they can ultimately imbue their setup with excellent stability. “Overall, we want to empower scientists to get the analyses done in a radical new way that’s very quick and worry-free so they can instead just focus on the physics,” says Held.

Alex Held, a research scientist at the University of Wisconsin—Madison’s Data Science Institute presents ‘The 200 Gbps Challenge: Imagining HL-LHC analysis facilities’ at CHEP 2024. Credit: Peter Elmer (Princeton University)

Based on all they learned during the Challenge, the research team is already setting themselves a new benchmark of 400 Gbps—doubling the already unprecedented data rate levels obtained. Remarkably, achieving these even more blazing speeds is not expected to require significant new hardware or novel software tactics; team members feel that they can wring still greater flow rates out of largely what’s at hand with innovative thinking and collective diligence.

“The history of high energy physics has always been to push the large-data frontier,” says Lundstedt. “We’re excited to have this opportunity to contribute to pushing that frontier into the 200-gigabit, even 400-gigabit space.”