Among the many impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic was the loss of an important research experience for many students, from first year undergraduates to PhD candidates looking to learn new skills: the in-person summer research internship. Closed campuses, travel restrictions, and uncertain funding meant that many students planning on working in university, government, and industry labs saw their summer postings evaporate. But while other institutions had to cancel summer programs, IRIS-HEP found itself in a unique position to re-envision and expand its fellowship program, offering more students the chance to try their hand at building software for high-energy physics,—and learning critical skills in the process.

“IRIS-HEP is a distributed institute, that’s just how we work,” says Peter Elmer, director of the institute’s PI and Executive Director. This distributed teamwork typically involves a lot of travel, so the institute had previously budgeted significant funding, largely from NSF participant funds, for getting people to in-person training and seminars. “The pandemic, of course, took travel off the table,” says Elmer.

“We looked around and said here’s an opportunity: unlike things that actually require people to be in a physical laboratory, turning knobs or operating instruments, we can do software work in a fairly distributed way. So it’s very natural to try and engage people who suddenly can’t work in a lab in our software research.”

The institute was already slowly building up a research fellowship program, —training about six fellows each year, —but in response to the pandemic, the institute dramatically increased the size of the program, accepting 16 fellows this summer alone, with more opportunities throughout the coming academic year. All fellows are working remotely, often in different time zones from their assigned mentors, but this too plays to IRIS-HEP’s strengths, says Elmer: “We were particularly ready to adapt to this, because people are already used to working in a geographically distributed way.”

A fellowship that was there when others weren’t

The expanded fellows program came at an ideal time for David Liu, who will be starting his PhD in physics at the University of Washington this fall. “Initially I was planning on going back to Caltech and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where I’d worked in previous summers,” says Liu. “But with the pandemic the opportunity to do things non-remotely is pretty much non-existent.” Instead, he contacted Gordon Watts, the Institute’s co-PI and a professor at the University of Washington, and ended up applying and being accepted for an IRIS-HEP fellowship, working from his home in Ohio for the summer.

Liu is working on testing infrastructure for ServiceX, part of the institute’s efforts in Data Organization, Management, and Access (DOMA). ServiceX aims to be an important tool for physicists who want to pull information from the pools of data generated by detectors like ATLAS. ServiceX uses a pair of “transformers” to filter and deliver only the data its users need. But the two transformers were developed separately—one for Python and one for C++—so there’s no guarantee a request made in one language will deliver the same set of data as an identical request in another. “Regardless of which programming language you’re using you should be getting the same information, because the data is just the data,” says Liu—so he’s working on testing the transformers to provide this guarantee.

“It’s been a great opportunity to start working with scientists from all over the world,” says Liu, who hopes to continue working on CERN projects throughout his graduate career.

New fellowships, new physicists

While some fellows, like Liu, are already in physics graduate programs, expanding the fellowship program allowed IRIS-HEP to bring aboard undergraduate and masters students—those earlier in their research career, who weren’t currently funded with a fellowship or graduate appointment.

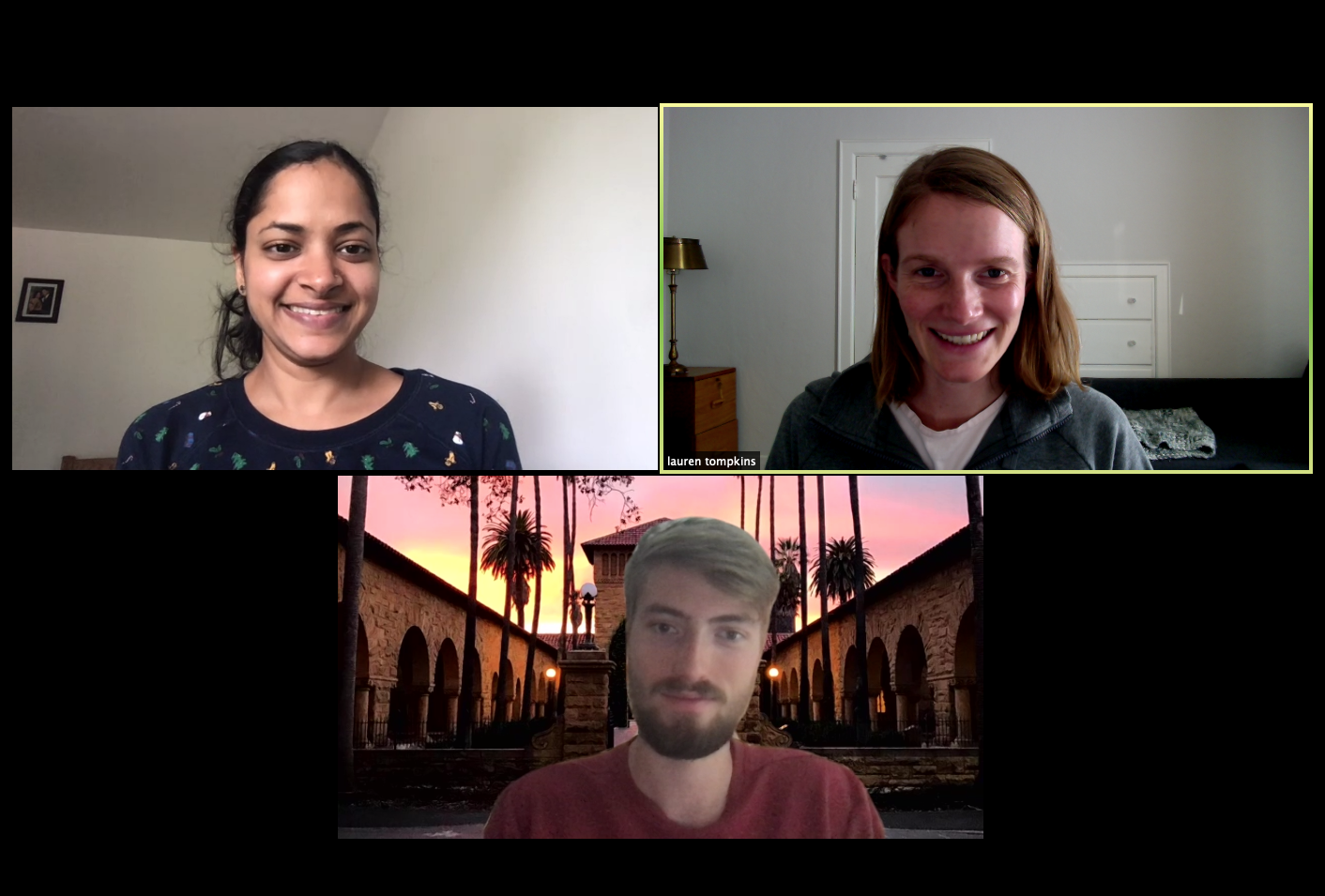

Lauren Tompkins, Assistant Professor at Stanford University (right), Rocky Bala Garag, Postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University, (left) and Peter Chatain, undergraduate student at Stanford University (bottom) meeting virtually to discuss Peter’s project – “Example Track Seeding Algorithm for ACTS”. Photo credit: Lauren Tompkins, Stanford University.

One such fellow is Peter Chatain, a rising junior at Stanford University. Chatain is working with Stanford Professor Lauren Tompkins on ACTS, a project in IRIS-HEP’s Innovative Algorithms area to create a toolset for particle tracking that can be used with any particle detector. “I’ve always been excited about physics, since sixth grade,” says Chatain. “And I’m also really interested in computer science, so I could see myself going into research in this direction.”

Chatain is implementing a sample “track seeding” algorithm, which generates a first guess as to how a detectors’ observations can be explained by actual particle tracks, which will be used in testing and expanding ACTS’s functionality in the future. “This is a nice project from a learning perspective,” says Tompkins, “because an undergrad like Peter can come in and contribute in a concrete way to an international effort. That can be challenging to find.”

Tompkins, Chatain, and Rocky Garg, the postdoc in Tompkins’ group who is mentoring Chatin directly, have had to deal with another wrinkle of the pandemic: Garg and Tompkins both have small children at home, so sometimes have to meet with Chatain at odd hours. “The flexibility of Peter [Chatain] and other students has been really helpful,” says Tompkins.

The legacy of mentorship

ACTS is part of IRIS-HEP’s mission to provide software that’s useful outside the Large Hadron Collider, whether to the broader data science community or, in the case of ACTS, other high-energy physics experiments. This not only provides tools that other scientists can use, says Elmer, but also “broadens the base” of programmers maintaining IRIS-HEP software, which makes it easier to maintain as LHC increases the luminosity of its beams in 2023 and beyond. But it’s not just new tools that make the software more sustainable. By introducing new researchers like Liu and Chatain to IRIS-HEP, the fellowship also sows the seeds for future projects by the fellows themselves.

Matthew Fecikert, a postdoc at the University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign who is mentoring IRIS-HEP fellow Bo Zheng this summer, is one example of how that can work. Feickert was introduced to DIANA-HEP, a predecessor project to IRIS-HEP, through the former’s fellowship program in 2015. Before his fellowship, says Feikert, “I was a typical physicist working on an LHC experiment. I was proficient in C++ and knew how to use python to glue together different tools and projects, but I didn’t have any bespoke software engineering skills.”

A cafeteria conversation during his fellowship at CERN led Feickert and fellow CERN researcher Lukas Heinrich to develop pyhf (python histogram factory), a python tool for applying different machine learning tools to data presented as histograms—as much particle physics data is. Users can compare the performance of different machine learning backends on their particular problems, speeding research dramatically. Just a few years later, pyhf is “the tip of the spear for the entire analysis systems workflow” says Feickert, and he’s training fellow Bo Zheng to help continue that work.

“I enhanced my ability to do research independently and to work in an English environment, and my open-source coding skills,” says Zheng. “I would like to do more research with IRIS-HEP in the future.”

The sky’s the limit

Other fellows have no plans to remain with LHC, instead taking their newfound skills to entirely different arenas. Aneesh Heintz is an aerospace engineering PhD student who plans to work in industry after he graduates, but that didn’t stop him from finding a wonderful fit in a project under Princeton professor Isobel Ojalvo. The two are among the IRIS-HEP researchers working to implement graph neural network models on hybrid FPGA-CPU chips, a customizable setup that rivals the performance of GPUs at a fraction of the energy cost. “One of the great benefits of FPGAs is that they’re far more energy efficient,” says Heintz. “That’s something you have to account for when dealing with massive detectors,”—Heintz’s project will help accelerate the ‘trigger’ for track-finding analysis, a process that must be sped up by orders of magnitude for the high luminosity era—”but it also means FPGAs are often used in aircraft and spacecraft.”

“I think the projects that I found was a really good fit because I’m able to venture into more of an avenue where I’m practically implementing deep learning models rather than developing machine learning theory, which I have done in the past,” says Heintz.

Elmer says IRIS-HEP is as proud to be training aerospace engineers as it is physicists, and that he hopes future iterations of the fellowship program will reach even more people, from all fields and backgrounds, and inform IRIS-HEP programming even after the pandemic.

“It’s not just a question of getting by,” he says, “it’s an opportunity to rethink how we do things. When this is all said and done we’ll have a better fellowship program than we started with. That would be a positive outcome from what is otherwise an extremely challenging situation.”